by Barbara Cervone

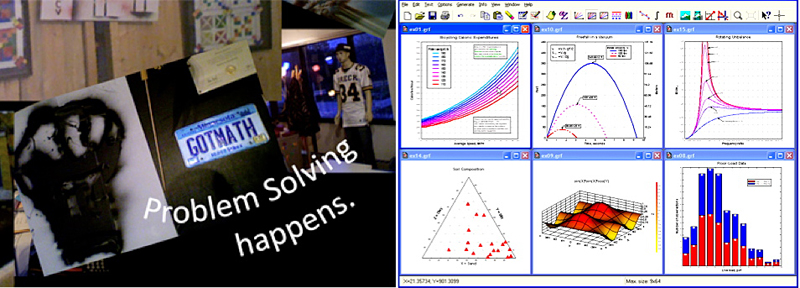

MINNEAPOLIS, MN—What if math and humanity played chicken? What if math swerved? What if math had more than one right answer? What is math good for?

A year ago, advanced math teacher Brad Kohl posed these questions to his students and fellow faculty at the Breck School in Minneapolis, Minnesota. For twenty years the private school, known for its diverse student body and strong academics, has encouraged juniors and seniors to engage in independent research projects in science and the humanities. Called “advanced research,” Kohl and his colleagues wrestled with how to shape a comparable program in mathematics—a program that would combine academic rigor with social values.

“We finally came up with the idea,” Kohl explains, “of offering promising math students a chance to identify and solve real problems in the community. “ Working as a “consulting mathematician,” the students would collaborate with a host organization to identify areas of inquiry, determine appropriate research and analytical methods, gather data, analyze results, and make specific recommendations.

This fall, two advanced math students took up the offer—and the Advanced Math Research program at Breck set sail.

Connecting Iranian-American youth

Senior Omead Eftekhari, the son of two Iranian parents who came to the U.S. after the 1979 Iranian Revolution, is working with The Foundation for the Children of Iran, a group that brings Iranian children to the U.S. for life-saving treatments that are otherwise unavailable. He is experimenting with different social media and messages to determine the most effective way of reaching Persian college students and young professionals as part o f the Foundation’s fundraising efforts.

f the Foundation’s fundraising efforts.

“There’s an older generation of Iranian donors who have come to the U.S., done well, and remain close to the country where they grew up,“ Omead explains. “But the next generation the ones either born in America, like me, or who left Iran in their youth need to be cultivated as potential donors.”

Omead began his task by constructing a survey that would gather from Iranian high school and college students much needed demographic and personal information. Creating the survey was the easy part, it turned out. Finding and recruiting students to fill out the survey has been the hard part—a test of the networking power of Facebook and other social media.

“We’ve reached about 50 leaders of Persian student groups across the country, mostly on college campuses, but now we need to reach the thousands of individual students who are part of these groups,” Omead says. “What makes this project difficult is that it is human-based: you don’t know when you’ll hear back from these people and what their responses will be.” It pairs the algorithms of social networking and survey data with the unpredictability of human nature.

For Omead, the project’s focus has also changed. “It began as a fundraising effort, but it has moved towards using social media to create a culture of connection, building relationships among Iranian-American youth nationwide that previously did not exist.”

Creating equitable assessment fees . . . and more

Nick Thyr, a junior, has taken on an entirely different challenge: helping city engineers in the Minneapolis suburb of Golden Valley devise an equitable assessment formula for the planned reconstruction of one of the city’s major intersections. In the past, the city has used the front footage to determine the fee adjoining businesses must contribute to the reconstruction: the larger the front footage, the higher the fee.

“The problem with this approach,” Nick explains, “is that it doesn’t take into account other factors like traffic flow and parking.” The amount of cars a business puts through an intersection in a given period of time, he hypothesized, is a key factor in what wears down an intersection. “Or take a business on a dead end,” Nick says. “By the old formula, the business would contribute nothing because it had no front footage, even though it might be putting a lot of cars through the intersection.”

“The problem with this approach,” Nick explains, “is that it doesn’t take into account other factors like traffic flow and parking.” The amount of cars a business puts through an intersection in a given period of time, he hypothesized, is a key factor in what wears down an intersection. “Or take a business on a dead end,” Nick says. “By the old formula, the business would contribute nothing because it had no front footage, even though it might be putting a lot of cars through the intersection.”

Nick’s formula, which includes traffic flow data along with physical footprint, would fix assessment fees such that all businesses paid their fair share.

“Sure, the math I’m doing involves statistics, number crunching, linear regression, but it isn’t rocket science,” Nick says. “The challenge is applying the math to analyze and fix problems in the real world. It’s gratifying when you can turn complex data and into a simple solution.” The city engineers at Golden Valley are just as thrilled, hoping to apply Nick’s assessment formula to future intersection projects.

Six months into the program, fourteen students have already submitted proposals to participate next year. One of the students, Brad Kohl says, has proposed developing a model that can predict upcoming political hot spots around the globe, then target preventive resources. She intends to collaborate with a Minneapolis-based world peace organization.

Already, Kohl says, the program is measuring up: “As you can see, this is not about telling students what to do, but about helping them ask important questions.”