|

by BARBARA CERVONE | DECEMBER 22, 2015

Entering the spare center of Kambi ya Simba, a 19 kilometer trip up a dirt road from one of Tanzania's main safari routes.

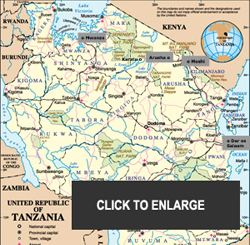

IN DECEMBER 2004, serendipity brought me across the globe to the remote Tanzanian village of Kambi ya Simba. Not far from Mt. Kilimanjaro and the vast Serengeti, this was a place where the road ended. For those who lived here, fortunes rose and fell with the crops. Villagers illuminated the night with lanterns and gathered water from distant pumps. The following summer, twelve youth from Kambi ya Simba joined with me to capture their daily lives in photographs and words. The nonprofit organization I founded published the resulting book, In Our Village: Kambi ya Simba Through the Eyes of Its Youth. Within a year, In Our Village had planted seeds of interest far and wide, reaching students in schools around the world. Touched by the stories from Kambi ya Simba, those other youth began to share their own. This narrative traces what has happened in the decade since. A scholarship fund generated by our book’s sales has sent more than two dozen youth from Kambi ya Simba down the Rift Valley to further their schooling. Donations to that fund also came in from U.S. schoolchildren moved by In Our Village. Over the years, some members of our writing team have kept in touch by email. We had the good fortune to reunite in 2014. These young authors have traveled far; all are college graduates now. In one of the world’s poorest countries, however, they continue to make sacrifices. They carry their parents’ hardships on their back, their own accomplishments and disappointments in their pockets, and hopes for their own children’s futures in their hearts. Barbara Cervone

porridge; checking in; crossing a dry riverbed; walking the village trails.

A dozen students from the village secondary school had walked with me for an hour to record Yame’s stories, taking his picture on the blanket where he greeted passersby. “Some days I worry for our village,” he told the students. “The rains are fewer. The soil is poorer. But we are a strong people. We care for each other.” That was the summer of 2005. Six months earlier, my family had visited the micro-loan program that our son, at 22, had started in Kambi ya Simba. As in so many villages across sub-Saharan Africa, I learned, life here depended on the bounty of each year’s harvest. Everything was scarce, and growing scarcer still. At a ceremony in our honor, villagers offered us what they had: a modest buffet seasoned with greetings, songs, dance, and humor. Towards the end of that reception, Henri Malle had taken me aside to whisper a request. He was the headmaster of Kambi ya Simba’s secondary school. Might our family donate money for a teacher’s dormitory? From thin air, I pulled a different idea. What if, instead, a group of students were to act as photojournalists and tell their village’s story? Proceeds from a resulting book could support those youth in continuing their education beyond what the village could provide. With a handshake and a hug, we two sealed the plan. The next summer, I returned for two weeks to make it happen. Twelve students walked the dirt trails with me, crisscrossing the 40 square kilometers of Kambi ya Simba. Using digital cameras and voice recorders for the first time, they

gathered photographs and interviews. They needed little coaching. Everything held interest, whether it concerned how to cook maize porridge or the Sunday service at the Lutheran church. Each night, I organized that day’s images and words to share with them. Without electricity, I worked under a kerosene lamp, fretting about my laptop’s battery and wondering when the cows in the adjoining shed would settle down to sleep. No one outside their village would care about their story and their lives, these young photojournalists told me at the close of our work together. But they were wrong. In fall 2005, our book made its debut, published by Next Generation Press, the publishing arm of the nonprofit that I lead, What Kids Can Do. Ten years later, In Our Village: Kambi Ya Simba Through the Eyes of Its Youth has sold more than 10,000 copies. It has inspired an international movement of comparable photo essays, In Our Global Village, which includes more than 60 titles created by youth on five continents. All twelve of the book’s co-authors have now completed teaching or university degrees. Profits from our book have helped two dozen Kambi ya Simba students attend postsecondary schools far from their village. Many are the first in their families to go past primary school.

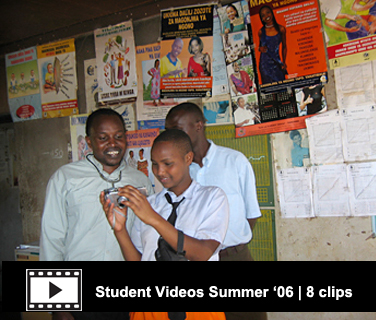

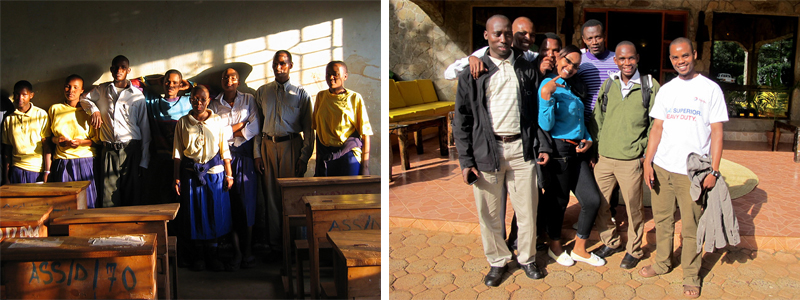

Ironically, just after I presented his copy to Pius, the headmaster placed that student at the center of a circle of his classmates and teachers to receive a public punishment. (I never learned what he had done wrong.) As Pius knelt to accept a mild thrashing, he held our volume in his fist. Passing me ten minutes later, he pointed to the book. “This makes me feel that I can touch the sky,” he said. On this visit, our writing team took a try at videotaping scenes around the village. They also recorded interviews with the headmaster, the village doctor, and each other. In March 2008, I returned to Kambi ya Simba again, to present the first scholarship awards from sales of In Our Village. Nine students, each accompanied by family members, filled a science lab classroom at Awet Secondary School, which now had a new blackboard and windows. The headmaster, who was supposed to officiate, was called away at the last minute, but Thomas, one of the scholarship recipients, took his place with enormous poise. He encouraged the participants to speak from their hearts, and translated between English and Swahili so that the parents could take part in the conversation. Students shared their dreams—to become a doctor, a teacher, a journalist—with a piercing determination that their own success would also lift their parents. In barely audible voices, their parents shared similar hopes. After that, my contact with the students consisted of email exchanges with the handful of them who had smartphone or computer access. Thomas was a regular correspondent. His studies placed him first in Karatu, 45 minutes from Kambi ya Simba on a rutted dirt road, and later in Arusha, two hours away. He described each of his subjects and wrote of his progress in school: “God willing, I am going to do well in all of my exams this term, I study every minute that is possible.” His father had died when Thomas was ten, and he told of the challenges of supporting his mother and sisters. “As to my mother she is getting better in her illness. Thank you for giving your recommendations.” Of poverty, Thomas wrote, “The cruelest part about poverty is that it fails families it fails children it fails societies.” Sometimes he offered me advice. On the day of the 2008 U.S. presidential elections, he sent me an email reminding me to vote—for Obama: “This is a major day in the history of the world. Obama is the future. If I lived in your country I would walk all day to place my vote.” Romana, the daughter of a teacher and a farmer, shared and updated her plans to both teach and farm, selling crops to schools in the area.

In Tanzanian tradition, the students invariably addressed me as “Madam” or “Mum” and ended their notes with God’s blessings.

To set apart the scholarship money from our book profits, I created a separate nonprofit, called New Assets, early on. New Assets also received and distributed donations toKambi ya Simba from students in the United States who had read the book and wanted to reach out. Among other improvements, their efforts provided beds and solar power for the infirmary, a water catchment system for the elementary school, a student mural project (which yielded colorful maps of Africa and diagrams of the digestive and reproductive systems), and basic school supplies. Thomas acted as our able, paid liaison for all of these endeavors.

(L) Young photojournalists in a classroom at Awet Secondary School, August 2005; (R) Reunion, Bouganvillea Lodge at Karatu, May 2014

“Do you understand me?” I asked, realizing that they were accustomed to British English and scripted instruction, not my mode of speech. The students stared back in silence. Then the headmaster, Henri Malle, rephrased my question: “Are we together?” Eagerly, the students nodded yes, and began listing possible topics for our book.

From then on, I made a habit of asking, “Are we together?” several times a day. In the winter of 2013, our group came up with the idea of a reunion. I would fly to Tanzania and we would gather as best we could, catching up on our lives, our challenges, and what gave us strength. Thomas volunteered to organize it all. We could not track down four members of our group, though we knew they all had earned post-secondary degrees. But on a sun-drenched morning in early May 2014, the Karatu “branch” of our group gathered at a gracious lodge outside town, along the road to the Serengeti. We hugged, passed around cell phones with our pictures, and then linked arms in a circle—Pius, Romana, Lucian, Fredy, Reginald, Thomas, and I—and asked for God’s blessings. Joseph Ladislaus joined us: the Awet Secondary School biology teacher who had championed our project nine years earlier, and now taught in Karatu. Later, I flew 500 kilometers to Mwanza, on Lake Victoria, to meet with two more students, Heavenlight and Triphonia. From there it was 1,200 kilometers to coastal Dar es Salaam, where I spent a day with Shangwe, whose studies and work had taken her the farthest.

Clockwise from top left corner: Maasai herdsmen near Ngogongoro where Reginald teaches; student assembly at Florian SecondarySchool in Karatu where Lucian taught; students at Mashingia Secondary School in Moshi where Romana teaches; Karatu branchoffice of the Tanzania Farmers’ Association where Pius worked.

Now, these young people were attempting to find their way in Tanzania, where youth unemployment (except in farming), hovered at 75 percent. Teaching—the employment most available to them—stood at the bottom of the professional ladder, paying poverty-level wages.

Reginald, the first to speak, spaced his words carefully. “My circumstances, I would say, are one part opportunity—and one part disappointment.” He had earned a teaching certificate a year earlier, in a three-year program sponsored by the government. When his job assignment ame—through an elaborate pecking order administered by the Tanzanian government—he found himself in a remote secondary school near Ngorongoro Crater, teaching the sons and daughters of Maasai tribesmen. In college, Reginald had confronted the limits of rote education; he had ideas about how to better engage students. Teaching children who would follow in their parents’ nomadic footsteps, in a landscape with no visitors, he felt discouraged and alone. In time, he figured, he’d secure a transfer to a better school.

Lucian spoke next, then Pius. Both earned bachelor’s degrees in science from the well-regarded Sokoine University of Agriculture. Lucian’s degree was in aquaculture; he dreamed of securing a job with the Tanzanian Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security. When his application was denied, he took a temporary position teaching biology and agriculture at a secondary school in Karatu. Lucian’s face lit up when he described his biology lessons. But he envisioned starting a business that would raise and sell poultry “broilers” to tourist camps and lodges. As the oldest of ten, with his peasant father barely able to feed the family, Lucian desperately sought the wherewithal to cover school fees for his younger siblings. “This is my first responsibility, from the heart,” he said.

Resume in hand, Pius went door-to-door for two months after graduation. In Arusha and then Karatu, he asked to be considered for any job opening, and his strategy paid off. He was first in line when a branch manager position opened up in the Karatu office of the Tanzanian Farmers Association. Proudly he demonstrated the intricacies of planting maize seedlings to face the sun in the field he had established behind his store office. “Farming is a science,” he said. A few months later, however, Pius had to resign from that position; he had developed allergies to the fertilizers that drew customers. Back on the job market, he was hoping to scare up enough money to pursue a master’s degree. His confidence was as big as his smile. “I need to be somebody special, to have people call me, ‘Dr. Pius, Professor Pius.’ I need to increase my level of study. I am 27. I am still young, still strong as can be.”

Romana’s gregariousness and determination put her in the lead as we walked the dirt trails of Kambi ya Simba in the summer of 2005. Recorder in hand, she tracked down the village’s only tractor-owning farmer and pressed him for details: How had he managed to acquire the most valuable possession in the village? What system did he use in sharing the tractor, for a fee, with others? At the time of our reunion, Romana was teaching at a secondary school in Moshi, a town of roughly 200,000 known for its universities, medical facilities, and prime location at the base of Mt. Kilimanjaro. There she earned a bachelor’s degree in education from Mwenge University College of Education. With friends, she also started a small non-governmental organization (NGO) to teach the importance of environmental conservation, saving money, and service: “items our society knows little about,” she said. And she rented a farm with several acres; in two months, she would sell her first crop of maize and pigeon peas. “I hate poverty and that’s why I work hard,” Romana said. “I wish for changing my life.” Thomas told his story last, leaning forward intently as he grappled with its elements. For six years, he had managed the New Assets scholarship fund and the projects that resulted from donations to the village from U.S. schoolchildren. Twice he hosted small groups of American teachers who had read In Our Village with their students and wanted to spend a week in Kambi ya Simba; once he hosted a whole class of students from Indianapolis who had spent a semester studying Tanzania. His skills and fluency in English won high praise.

Another summer, Thomas arranged for the scholarship winners that year to tutor at the village primary school; later, he submitted a ten-page report on that. Studying hard, he graduated with a degree in computer technology from a college in Arusha whose tuition he could afford. Though he earned the least of anyone in the group, he remitted most of his New Assets stipend to his mother and younger sisters. “I have tried my level best at everything I can, everything I do, but I have yet to find employment,” Thomas began. But, after subsisting for so long on hope, he had grown discouraged. He applied for several jobs that seemed suited to his skills, with poor results. An unpaid internship that he secured, in the information technology department at a government office in Arusha, convinced him that “my college studies did not train me adequately and my will is not enough.” Although he enrolled in several private courses to acquire more technical knowledge, he feared he would not catch up in time to win praise from his superiors. Thomas looked to the group for advice. For the rest of that day and the next, our group talked long and hard about strategies for getting ahead, family and responsibility, faith, and the social harm that flows from Tanzania’s chronic failure to invest in education and opportunities. “Our contributions could be huge,” said Reginald. “I so want to be done with poverty,” Romana added. We also laughed and teased each other, and feasted on a generous lunch both days. The lodge’s outdoor pool went untouched. Except for me, no one in our group knew how to swim. We closed, as we had opened, with a prayer. “Thank you, Father, for these three days,” began Joseph, a teacher. “You were with us, and we did it well.”

Heavenlight, too, earned her bachelor’s degree in education, which in theory gave her an advantage in teaching assignments. (In contrast, new teachers with only teaching certificates, like Reginald, are sent to the most remote schools with the poorest conditions.) Nonetheless, the government placed her in a rural school in northwestern Tanzania, while her husband, whom she had met at university, worked in Dar es Salaam (known as Dar). Their two-year-old son lived with Heavenlight. Separated by a thirteen-hour bus ride, the family came together only three times a year, on school holidays. Heavenlight requested a transfer to Dar, but the competition is tough for teaching positions in Tanzania’s capital. “Many things make me happy when I’m teaching,” she said, undiscouraged. “It makes me forget my problems.” There were sad times, too; every Friday, Heavenlight counseled students struggling with early pregnancy, drugs, and HIV. Like her pupils, she coped with malaria (a given in this region) and water-borne illness (buying four buckets of water a day for her needs). She took pride in the small business she began, embroidering and selling bed sheets: “I feel like an independent woman, providing for myself.” An only child, she shared her earnings with her mother. Of her little boy, she said, “He is my world. I need him to study hard and become a doctor someday.”

For Triphonia, a medical career was close at hand. On my second day in Mwanza, I hired a taxi driver to drive two and a half hours—a third on unpaved roads—to Mkula Hospital, where she was completing her fieldwork, the final stage of her medical education. After she finished her advanced secondary studies, Triphonia had married Joseph, who was her biology teacher at Awet Secondary School and part of our writing team. Joseph had hoped to earn a university degree in wildlife management but could not afford the tuition. They settled in Karatu, where Joseph taught secondary school; he earned extra income tutoring physiology and biology to nursing students, and raising and selling pigs on the side. They had a child, Justin. Determined to get ahead, the couple agreed that Triphonia would pursue a three-year clinical officer program in Mwanza, even though that meant leaving Joseph and their son in Karatu. When my taxi finally pulled up at the rural hospital (run by the African Inland Church of Tanzania), Triphonia ushered me past a small crowd of men, women, and children at the entrance. She showed me the dispensary, a dark room stocked floor to ceiling with medicines, and then the blood lab, where several patients were receiving transfusions. In the pediatric malaria ward, Triphonia moved among her young patients and their distraught parents, adjusting IV tubes and checking charts. “By the time these children arrive at the hospital,” she told me, “their severe malaria has produced severe anemia and their chances of survival are not good. Some go into cardiac arrest. It is so sad.” She showed me the bare operating room, where she assisted with surgeries for complicated pregnancies, and the adjoining recovery room, where some infants seemed to be fighting for life. “I hope this is not too much,” Triphonia said. “I thought you should see what medical conditions are like here—what it is that I do, who are the sick.” She hoped to continue her medical studies and someday become an advanced medical officer (one step short of a doctor) who led patient care in cases of acute illness. “I want to treat patients who get well,” she said. From Mwanza, I flew to Dar es Salaam.

Shangwe insisted on picking me up at the airport, in her new car. Stuck in the gridlock common to exploding cities in the developing world, she was two hours late. We drove to the tall, modern office building where she worked as a human resource officer for a large, autonomous department of the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare that procures, stores, and distributes medical supplies country-wide. Shangwe had earned a bachelor’s degree in human resource management at one of Tanzania’s top universities. This was her first job, and she was justly triumphant. At Awet Secondary, she had been one of the highest performing students. She had support and encouragement from her mother, who taught primary school, and from her father, who had managed to turn farming into a business. Sitting at her desk and bursting with confidence, Shangwe talked about translating her schooling into practice. “I know the hard skills—now I’m learning the soft,” she said. “I welcome change. I am a good listener. I learn from other people. I like people.” She knew what she wanted: “To be a big-time human resource professional!” When the time was right, she said, she would pursue a master’s degree. Late that night, in the small apartment she rents with a friend, Shangwe and I completed the conversation started earlier. Preparations for an upcoming workshop had kept her at the office until eight in the evening. “I work as hard as I can,” she told me. “I want to help others achieve what I hope for myself—to move from where I am to where I want to be.”

Leaving poverty behind. Finding a decent job. Being responsible. Getting ahead. Helping earlier generations and the next. Preserving faith. Being strong. Being someone special. Moving from where I am to where I want to be. These were the goals our group shared when we first walked the dirt trails of Kambi ya Simba, and these are the goals they continue to embrace. Now in their mid- to late twenties, they have traveled far beyond what seemed possible, coming from a place invisible on most maps. They are not bound, like their parents, to the rains and the harvest. They have college degrees, resumes, and first jobs. Their worlds have grown. Yet the constraints weigh heavy. As of this writing, Thomas had served two more internships, but neither led to a job. He was recovering from tuberculosis. Pius remained unemployed after his allergies drove him from the Tanzania Farmers Association; short of funds, he temporarily abandoned his hopes of earning a master’s degree. Reginald had a wife and a new baby, increasing his determination to escape his teaching outpost among the nomadic Maasai. Living 1,500 kilometers from her husband, Heavenlight continued to balance independence and longing, teaching school and raising their young child alone. Triphonia, degree in hand, worked in a small clinic 20 kilometers from Karatu, where her husband and child live. She cared about her field, but a lack of public transportation meant that she was only “home” on weekends. Lucian, with his bachelor’s degree, secured a job at a private school in southern Tanzania, where the pay was higher and the faculty was exploring project-based learning and entrepreneurship, a promising match for his talents. He still wanted to start his own business, determined to help support his nine younger siblings. Lucian recently married; like the others, he lived apart from his spouse, who was teaching in northern Tanzania. “We are young Africans and we are strong,” Pius declared, at the end of our Karatu reunion. “We are still making our path.” “And the paths of our children to come,” said Romana. In the din of the cicadas, our group stood in a circle and held hands. With the next generation, there must be no poverty, we vowed. “We are the bridge,” said Joseph Ladislaus.

A very special thanks to Cathryn Berger Kaye, international service learning consultant, who has championed In Our Village: Kambi ya Simba Through the Eyes of Its Youth with teachers and students around the globe.

What Kids Can Do, Inc. | info@whatkidscando.org | www.whatkidscando.org

|

||||||||||||