|

|---|

by Joanna Klonsky

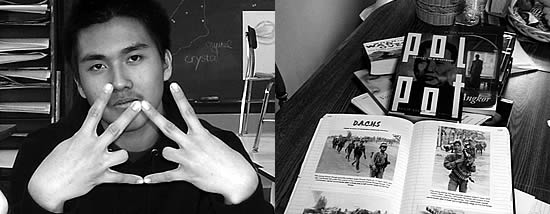

PORTLAND, ME—Tenth-grade humanities students at Casco Bay High School in Portland, Maine, don’t spend much class time drilling for standardized tests. They don’t memorize a lot of information from textbook chapters for homework, either. As human rights documentarians, there isn’t much time for that kind of thing. For the past school year, the students in teacher Susan McCray’s class have been researching human rights crises, as well as interviewing and photographing immigrants from places like Somalia, Sudan, and the Balkans, among others, who now live in Portland.

Not a “soft subject”

For his part in the project, tenth grader Charlie Hood interviewed Sophy Hang, a survivor of the genocide in Cambodia who escaped to the United States. “I conducted a series of interviews with her, asking her general questions at first, and then going into more in-depth questions,” says Hood. Hang was “very good about it, which was helpful for me because this is not a soft subject to be dealing with,” Hood says, “and when you’re asking questions about genocide and such, it’s helpful to have someone who has already talked about it with other people and can easily talk about it.”

The teens didn’t just jump into the interview process, however. McCray’s students went through extensive workshops on oral history and photography with Salt Institute Executive Director Donna Galluzzo. The classes focused on learning “how do you observe, how do you listen, what are you listening for, and how do you identify the essence of that person’s story,” says McCray, who designed the human rights–oriented curriculum. “How many people know how to sit down and truly listen to another human being?”

The students also conducted “classic research” and read related literature, including the autobiography of Paul Rusesabagina (of Hotel Rwanda fame), and What is the What, the story of the “lost boys” of the Sudanese civil war.

Being a subject and a student

Marcy Angelo, another of McCray’s tenth graders, conducted her own interviews with a freshman at Casco Bay who fled Somalia when she was a child during the civil war. But Angelo, who was born in Sudan, was also an interview subject for a classmate. Angelo’s family traveled to Cairo during the civil war in Sudan before immigrating to Portland nearly ten years ago. Being a subject for her classmates to study was “a weird and interesting and sometimes awkward—but very fulfilling—experience, because this is the first time I’ve really talked about where I come from,” says Angelo. “It was a way to be truthful to myself and to begin to integrate the two different sides of me that I do so well keeping apart,” she explained. “I’ve learned that I don’t need to be two different people.”

Marcy Angelo, another of McCray’s tenth graders, conducted her own interviews with a freshman at Casco Bay who fled Somalia when she was a child during the civil war. But Angelo, who was born in Sudan, was also an interview subject for a classmate. Angelo’s family traveled to Cairo during the civil war in Sudan before immigrating to Portland nearly ten years ago. Being a subject for her classmates to study was “a weird and interesting and sometimes awkward—but very fulfilling—experience, because this is the first time I’ve really talked about where I come from,” says Angelo. “It was a way to be truthful to myself and to begin to integrate the two different sides of me that I do so well keeping apart,” she explained. “I’ve learned that I don’t need to be two different people.”

“The Human Face of Human Rights”

In the end, the students created “amazingly sophisticated pieces of writing,” says McCray. They then produced black foam core panel displays holding their photographs of the subjects and passages from their interviews for an exhibit at the Salt Institute’s gallery. The show was called “The Human Face of Human Rights,” says McCray, “to show the world that behind these crises are real people.” She quotes a student: “It’s not just so that history won’t repeat itself—there’s also just something about universal collective awareness that itself changes the world.”

As for the project itself, McCray says that she hopes to do it again next year. It is rare to find such a curriculum in a public high school, but at Casco Bay, an “expeditionary learning” school that opened its doors last year and will have only 400 students when it reaches its maximum capacity, teachers enjoy more freedom than at other schools.

Although McCray describes the human rights curriculum as “intensely rigorous,” the students are enthusiastic. “It’s just so much better than sitting in a classroom, reading out of a textbook or taking tests or writing essays,” says tenth grader Stephanie Ewen, whose interview subject came to Portland from Zimbabwe. “We still learn all the types of things that other schools do, but we’re a lot more hands-on, and we actually go out into the world and make a difference.”